Welcome to our six-part video series exploring the topic of children at risk from a biblical perspective. Our goal is to shed light on how God sees and works in situations of conflict and danger that affect vulnerable children. Every month, we’ll release a new video that delves deeper into this important topic, offering insights and practical teachings.

So, get ready to join us on this journey as we explore the depths of God’s heart for children at risk.

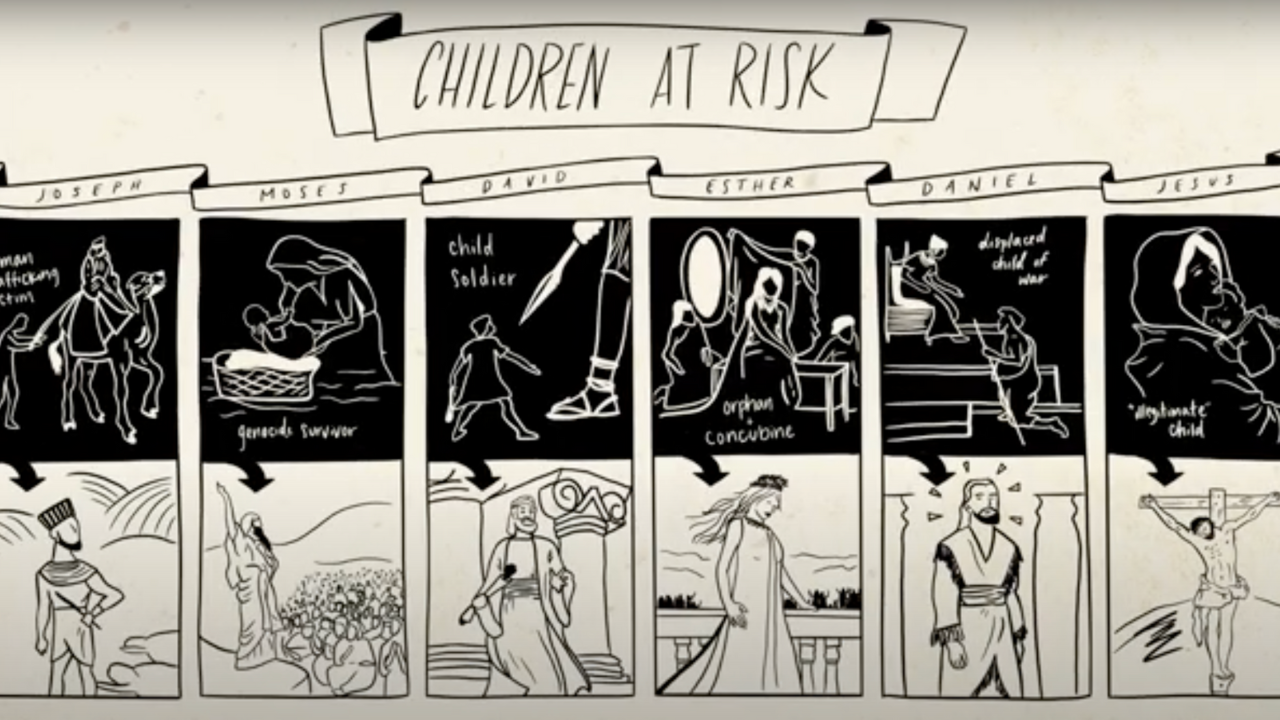

There is a pattern we can find in looking at many of our Old Testament heroes. They began as children at risk. Risk of violence, human trafficking, displacement, abuse.

So what constitutes a “child at risk.” It is basically someone under 18 and at risk of abuse, neglect, or some other kind of harm that needs outside intervention.

From a biblical perspective, that child is being blockaded from fulfilling their God-given calling.

I also want to offer some practical examples of how I take these biblical stories of God’s children into account when I develop strategies to protect, rescue, and empower God’s children at risk today.

My goal in exploring these stories and the stories of children at risk I’ve encountered is to be biblical, historical and technical while maintaining a spiritual depth.

I’m going to overview 6 Old Testament children at-risk stories that help us see a pattern of oppression, resilience, and impact.

These 6 case studies begin with marginalization and harsh injustice against these children. Eventually, they each grow through those injustices to become leaders who impacted nations. Each of these children had advocates along the way.

It’s important to look at these stories because they are small case studies on how influence happens in nations and regions and how God moves.

First, we see Joseph, a human trafficking victim at 17 — later co-regent of the greatest economic superpower of the day. He protected his family line during a massive famine.

Moses

Then Moses, a regional genocide survivor at 2 years old, Rescued 1.5 million slaves. He developed into a prophet and a desert lord.

David

David was a child soldier, facing Goliath at 13 or 14 years old, and a child of an Ammonite concubine.

He became a great Psalmist, Prophet, and Warrior-King. A man after God’s own heart.

Esther

Esther was part of a foreign king’s harem, one concubine of a thousand chosen to sleep with the king. Probably 11-15 years old.

She was an orphan of the Diaspora by foreign conquest. She rises as a queen and a protector of her own people group from racial genocide.

Daniel

Daniel and his friends were internationally displaced by war. As a young teenager of 13-14 years, he became a slave, a prize of war.

He served 8 kings, of three empires. And he became a counselor to kings bar none.

Of course, we could end out this list by noting that Jesus would have been considered by many a child born out of wedlock.

John 8:41 alludes to this: So they said to him, “We, at least, were not born out of wedlock!” The shame and rejection of being considered an illegitimate child was a tough thing in the ancient religious community of the jews.

We see common threads of injustice, danger, and opportunity through all of these stories. But a model also emerges from their stories of empowering without extracting. This pattern in scripture places children at risk near the perpetrators of injustice and empowers them to bring bright light in dark places.

This is counterintuitive because our instinct is to extract the helpless out of a situation and not to empower them within the problem to be resilient. This observation in scripture is definitely not meant to divert the justice worker from being a strong advocate of rescue and of protecting children…

BUT we should be considering holistic approaches to rescue, such as restoring a child’s to their cultural environment or rescuing an entire community through a prophetic call or destiny.

In these cases, we have to ask broader questions about what opportunities may be available to create a bigger picture solution rather than only seeing a child’s situation as it impacts them in the moment.

I want to show you what I mean by this in practical examples:

While we would love to be able to pull all child soldiers out of the armies and into schools, this is not always realistic, so we have to find other creative solutions.

We have taught school to child combatants while they were active in the army.

We have programs where children are registered with a rebel commander’s camp but attend school most of the time and we have access to them and relationship with their families.

We have leaders who visit child combatants in military camps, pray, worship and teach them about Jesus.

We discipled a rebel leader of an army, and he began to educate his children, feed them better and had them sing in a choir!

This goes to show that if you can shift a leader’s agreement with justice several inches and you may help thousands of children.

We have to make holistic considerations when we are making decisions about children at risk. Here are some thoughts:

1. Consider whether you can restore a child in their community before extracting them from their location. Locally empowering their community to serve them.

2. Consider what the child needs for healthy growth. A family of love, a community of believers, the scriptures, spiritual and character development, basics like shelter, food sustainability. Education and empowerment. Can we provide those in their community or only in our own facilities?

3. Family has been a core foundation of society for thousands of years. Though family life can come in many flavors, parents and grandparents remain primary shapers of a child’s understanding of God.

How can we keep those people involved in a child’s life without putting them at risk?

4. Consider how you will help that young person become a leader with a just and peaceful heart one day.

A technical term that comes close to the idea of “local empowerment” versus extraction is “harm reduction.” Harm reduction is the strategy to reduce harms when a full stop rescue is not possible. This term is used especially with substance abuse behaviors when a complete fix is not likely but if fits in child protection spaces too.

A question we should always ask — is harm reduction versus extraction a possibility?

For example, parents often sell or give away their children because there is no option for food in the short term. Addressing basic needs or food sustainability can reduce trafficking.

Are we rescuing a child and stealing their destiny as God’s answer to their own people?

Each one of our old testament heroes were empowered in the heart of darkness to be leaders in the future.

Let’s not be scared of the dark. Let’s believe the light is powerful enough to shake a region into the purpose of God!

Something else important to note is that each one of these OT children represented some kind of significant transition for the people of God.

____________________________

- Joseph represented the transition to Egypt for the family, a period of growth and waiting for the promised land.

- Moses represented the transition from Egypt and to the promised land.

- David represented a transition into peace and prosperity for those promised land people.

- Esther represented a transition to a season of safety for a people in exile from the promised land.

- Daniel represents a new kind of people. Those “who live in Exile here” but shine brightly because they have the promise land in their hearts. He was a forerunner for us today and of Jesus, the light of the world.

Whenever God’s next big thing comes on the scene, it begins with a hinge between the older generation and the younger one

— how the older generations work with the younger generation always shapes the future.

So how will we work with the next generation of leaders, especially the ones in the darkest places on earth?