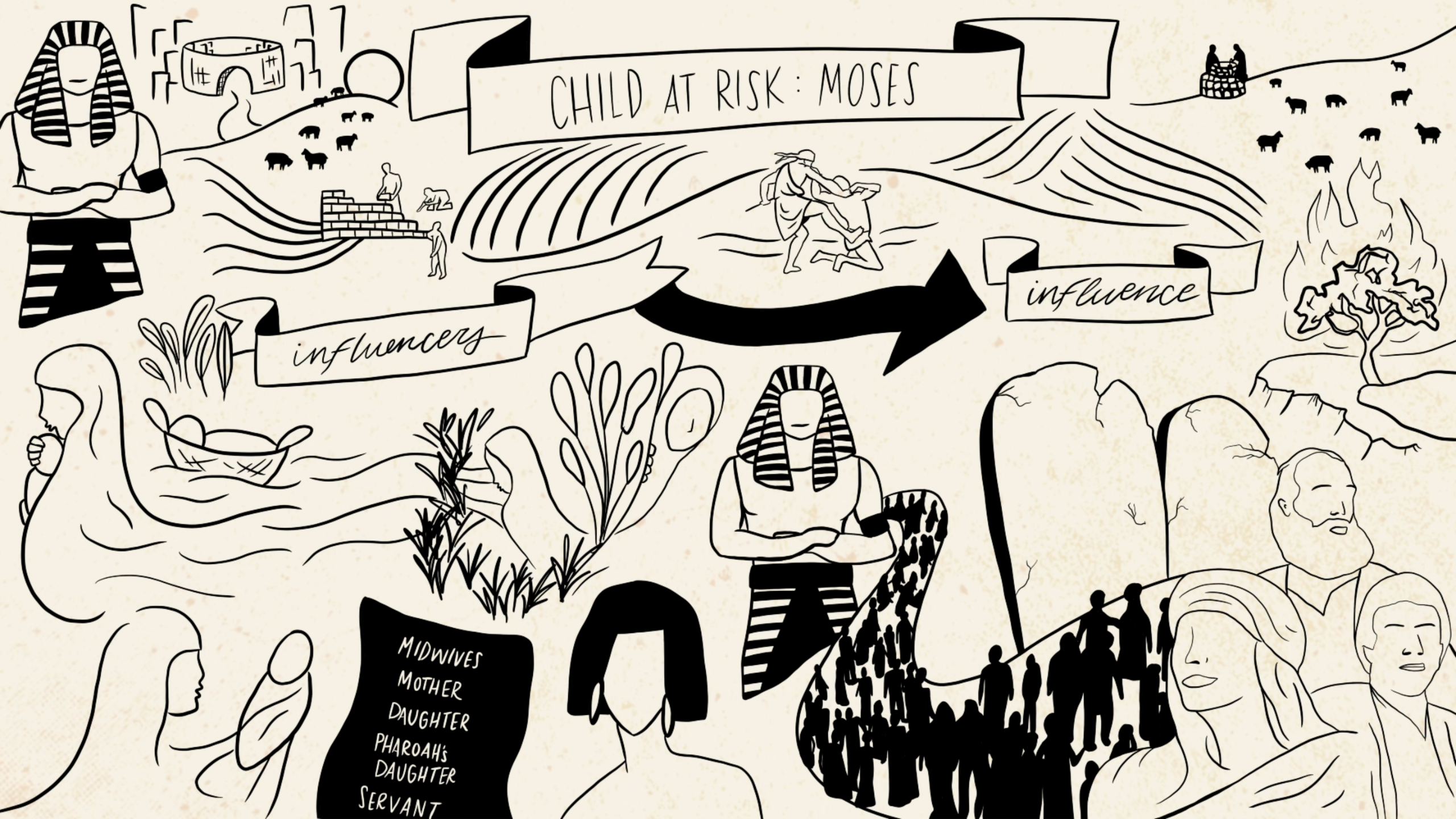

Welcome back to our six-part video series, where we delve into the gripping topic of children at risk through a biblical lens. In this third installment, we uncover the extraordinary journey of Moses, a survivor of genocide who emerged as the remarkable leader of Israel, leading them out of Egypt. Together, let’s bear witness to the awe-inspiring power of God’s redemption as it unfolds before us, immersing ourselves in Moses’ extraordinary narrative and extracting invaluable reflections that resonate with our lives today.

The pages of Moses’ story open more than 400 years after Joseph’s. The story begins in Exodus chapters 1 and 2 with Israel multiplying, intentions, and Egypt rising. In some ways, it’s a classic story of a more powerful people group oppressing a less-equipped one that we often see in places today like Myanmar or Colombia.

Dynamics at Play

There are a couple of dynamics at play here to paint the context. Centuries earlier, Joseph practically enslaved all of Egypt. He was enslaved to Pharaoh with his Keynesian economic policies.

And then the new Egyptian king of the period is thought to be Thutmose I, and he demonstrates no ancestral honor ties to Joseph’s past season of influence at all. But he did accept the continued practice of the central government’s ownership of people, and he moved into forced servitude of these Hebrews that were living in Goshen.

These Hebrews were Bedouin herders, and herders were considered lower class, and they were despised by the elite Egyptian culture. Thutmose I is believed to be a warrior and a powerful empire builder, and the Hebrew labor would have become important to his expansionistic reign. He is sometimes even called the Napoleon of Egypt.

The Hebrews were assigned to work into gangs under their slave masters. The nearly free labor allowed Egypt to build these store cities, likely near Goshen. The Hebrews were slaves serving under military rule. So this is our context.

Next in our story, we have Pharaoh, who orders a male child genocide to be overseen by the Hebrews midwives. The Hebrew birthing stool was a pair of two stones that the woman giving birth would squat on one leg on each stone, and the space in between these stones is where the baby comes out.

And the king commanded the midwives to kill the male child when he was delivered between these two stones. So some translators feel that the pair of stones is actually a euphemism more like if the child has a pair of stones, kill him. How could these midwives do such a thing?

The Bible is clear that as these midwives took the risk to fight for the lives of the male babies, God showed them favor. It’s a beautiful picture of those who stand for justice under extreme duress.

So let’s pause here for a moment and consider what situations God has put you in that offer a choice to go in a different direction than your culture or community. A different direction than everyone else doesn’t mean being opposite or being obstinate. It actually means seeking an alternative path from the Lord and being willing to venture down that path. So let’s think about this from the standpoint of pioneering. A pioneer sees a different picture of how the world could or should be. They gather that resolve and the resources to do something.

Our Hebrew midwives were pioneers in protecting children, not because they wanted to be experts but because there was no other good moral choice. They had been pushed into this different path. And if you want to become a powerful leader, you’ve got to learn how to consider how your decisions today will impact future generations.

It’s worth noting that the Hebrews persistently multiplied even with an active genocide mandate. So, history proves that the oppressed are often resilient and vigorous. The persistence of the midwives in the face of Pharaoh’s complaints exemplifies this.

So when baby boys continue to be born, King Pharaoh commands his own people, “Kill the sons of the Hebrews, throw them in the Nile.” Can you imagine how this worked? A whole society being commanded to become little baby boy snatchers or snitches. And it’s into this unimaginable reality that Moses is born.

InFire, our organization has worked for years in a rebel area in Southeast Asia where children are forcibly conscripted into the army. Now I have four children and imagining them being forcibly conscripted from my doorstep has often kept me motivated to stay the course, to continue to rescue and work with kids.

We actually know an army controlling a rogue state in Southeast Asia that does this. They run a census on a village, and this is village after village they do this with, and then they come into conscript.

If a family has two children, one belongs to the army. If a family has three or more children, then two of them belong to the army. The target age that they go for is 12 to 14, but we’ve seen many children, eight, nine, 10, 11 years old, which are also taken. We’ve had desperate parents contact us when the army is coming into conscript.

And think about this, what did it feel like to be a parent who had to throw their son into the Nile or watch somebody else do it? Did they curse God when a son was born instead of a daughter? Many parents’ hearts were shattered. Maybe there were other parents floating their baby boys down the Nile because it would have been too hard for some parents to watch them drown or kill them outright.

Now most commentators seem to think that removing the male children was to decrease the Hebrew population. But a few observations from other cultures may be useful here too.

Our Observations

Our first observation is that women are often the beasts of burden. They’re stoic and strong in their suffering. They don’t fight back as often as men do.

And the ethnic people of Myanmar are a good example because men may chop the wood, but women haul it on their backs. They’re also often taking the hardest task on, like hauling the water by hand a mile or two miles away during the dry months.

And then men lean towards making war, but women in many cultures are the more reliable servant class.

This isn’t just in Myanmar though, the International Labor Organization says that the inequity of labor is almost the same in rich industrialized nations as in the poorest countries.

A second observation is that by anthropological standards, women of most people groups will incorporate into another nation as a citizen by marriage far easier than a man.

They are accepted quicker, are seen as less of a threat, and will look out for the interests of their children often before racial differences.

These are certainly factors that could have played a role in Pharaoh’s reasoning. If we really want to be builders in God’s kingdom, we need to be wise to this wider range of socio-cultural issues.

The Holy Spirit will lead us, but He created us with the brain. So let’s be humble learners from this world around us.

Women are often less threatening as missionaries and as social justice workers. They often work harder and care in deeper ways for those they serve, with hearts full of compassion and deep intercession, and they can penetrate a target region coming in under the radar.

Pay attention to how God used women to preserve Moses’ life.

We first see this with Moses’ own mother, carefully concealing him for three months. And then she modifies the command of Pharaoh. She innovates, right? And she makes Moses a floating basket for the Nile.

And Moses is pulled from the Nile by a servant, while Pharaoh’s very young daughter is bathing in the river.

And then we have young Mary of his sister who’s spying from the rushes, who feels compassion for her tiny brother. And she slides out of the bulrushes, piping up, “Hey, do you need a nursemaid?” Moses ends up growing up with Pharaoh’s daughter and his, under the radar, mother turned servant, and nursemaid.

Can you see this theme of women throughout the story? Moses’ story? Midwives who stand up to a king, a mother and a daughter who fight for a baby’s future.

A daughter of Pharaoh who becomes the doorway to Moses’ education and his influence in Egypt. His preparation to deliver a million and a half slaves from Egypt. How else could Moses have ended up in this place? What Egyptian man would have had enough compassion?

So putting myself into the heart and the mind of Moses’ mother brings me both joy and also terror. “Oh God, oh God, my son lives,” she’s thinking right when he’s pulled from the water.

It’s an overwhelming and tearful moment of hope and thanksgiving. And then she’s thinking, “My son’s going into Pharaoh’s home, oh God, oh God.” So she’s got terror for his future, anxiety in this moment of rage or disinterest. “My baby could be killed. What’s gonna happen?”

Even though Moses was rescued from the Nile, he was still a child at risk. He’s being raised in the house of the oppressor of his people, his people’s chief enemy.

Not only did Moses enter that house, but in Exodus chapter two, we see his mother enters too. She carries that boy to the daughter of a king after she takes care of him after he’s weaned. And can you imagine what it would have been like to be a mom bringing that child into your enemy’s house for good?

Moses was likely a bit over three years old when his mother brought him with her to Pharaoh’s daughter. It was long enough that a deep bond would surely have developed and now she had to let go. She had to lose her access, let go of her right to protect the object of her love and trust her son into God’s hands. Without her release of the child, no leader or deliverer would have emerged.

So what valuable thing is God asking you to lay down so that the purposes of God can run forward? Yes, there’s a sting of injustice in this, but you need to know that something good is coming.

Moses’ mom got to test run, keeping Moses until he was weaned. She knew Moses was a special child, and so she fought for him.

Even though the long-term opportunity to raise him had to be given up, her choice of letting go of making the sacrifice of her son into the house of her enemy paid future kingdom dividends.

Later, her three children came together an amazing team of leaders at a time when they could really fly. Though it’s not in the biblical text, some scholars believe that Hatshepsut, Moses’ adopted mother, eventually became a follower of the Hebrew religion.

One of the signs of Hatshepsut’s possible faith is that she fought no wars, and at the end of her reign all the information about her was either destroyed or to face, which is usually a sign of forsaking the Egyptian gods. If this was the case, while she was co-regent with Tutt Moses II, the oppression of the Hebrews was likely very minimized.

And consider the possible impact Moses’ family had on the entire nation of Egypt through this relation with Hatshepsut. Also consider the impact they did have by fighting for the life of one boy, maybe two, as we know Moses had an older brother, Aaron, who also became a key player. And also consider it was these three siblings that led Israel into freedom, the freedom of the desert.

God does use families for his purposes. How does he want to use yours?

You probably remember the story of how Moses kills an Egyptian and has to flee. He becomes a shepherd serving a Midianite priest. Note that when he flees and rests at the well in Midian, it’s a woman yet again who advocates for him, and this time it’s with her father Jethro.

Interesting that it was the Midianites who sold Joseph and brought him into his desert season and it’s the Midianites who embraced Moses into his desert season.

Sometimes it’s our enemies who become friends or at least lead us to the place where God can equip us for the next season. When Moses returns after his burning bush encounter, it was to challenge Thutmose III, his Egyptian brother, and yet another conflict between brothers like we saw in the book of Genesis and the story of Joseph.

We know this continuing story of Moses, the signs performed in Egypt, and the open war against the Egyptian gods. Now we can recall the mass exodus of one to two million slaves who leave under the care of these three siblings.

There was a subsequent establishment of a religious justice system and this nomadic nation that reflects the presence in the reign of God.

Consider the Ten Commandments, which still influence ethics and justice around the world today. It is amazing all that we can learn from a child at risk who grew up in his enemy’s house.