via: STRATFOR Global Intelligence

The United Wa State Army, once recognized as the world’s largest narcotics trafficking organization and Myanmar’s strongest ethnic minority army, finds itself at a strategic crossroads amid broad changes to the country’s political landscape. Over the past decades, opposition to Myanmar’s military-led government both inside and outside the country afforded the Wa army a high degree of autonomy, allowing it to greatly expand its territorial control in northeastern Myanmar’s Shan State and to counter the junta with its economic and military strength.

However, the central government in Naypyidaw is pushing for national unity in support of its ongoing liberalization and normalization of relations with the outside world, and its intolerance of the Wa army has grown demonstrably. The government is now increasingly seeking to expand its presence in Wa territory in hopes of eventually drawing a region over which it has historically exercised little control into the national fold, clouding the Wa’s future. A full-scale military offensive may not be in either side’s interest, but Naypyidaw’s recent success in using a divide-and-encircle strategy has put the government in an unusually favorable position over the Wa, leaving the long-resilient ethnic militia short on leverage and forcing it to reassess its strategic options.

Analysis

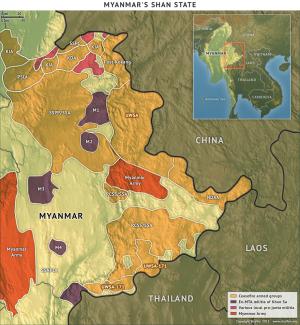

The United Wa State Army is the most powerful ethnic army in Myanmar, with an estimated 30,000 troops in its ranks, some 10,000 auxiliaries and near autonomy in the parts of Shan State it has controlled over the past two decades. As such, the organization has been perceived by Naypyidaw as an increasing threat to the government’s goal of national unification. Since March, Wa demand for a politically autonomous state has increased, and the Wa army has reinforced military posts over the past year amid concerns that the military, which has been fighting ethnic Kachin and Shan militias elsewhere in northern Myanmar, could soon focus its attention on Wa territory.

On July 12, the Wa took part in a new round of peace negotiations with the government amid rising tensions surrounding the United Wa State Army’s southern base in the 171 Military Region — a region near the Thai border that is roughly 150 kilometers (90 miles) from the area along the Chinese border officially granted to the Wa in Myanmar’s 2007 constitution. Since late June, the Myanmar army, known in the country as the Tatmadaw, has been increasing pressure on the Wa’s southern command, with the government demanding a list of bases on the Salween River, and it issued an ultimatum for the withdrawal of the Wa army from four strategic military outposts in Mongton and Monghsat — towns located along the Myanmar-Thai border that serve as critical supply routes for the Wa. The ethnic army has yet to give into the ultimatum, and both sides have continued reinforcing their troop levels throughout the region.

Evolution of the Wa

Perhaps best known as part of the drug-producing region called the Golden Triangle, Shan State has historically served as a battleground for ethnic insurgencies, drug lords, warlords and foreign powers, its geopolitical complexities exacerbated by the lack of central control. Alliances among the various armed factions in the border region are continually shifting.

The estimated 600,000 indigenous Wa living in northern Shan State emerged as a major factor in Myanmar politics in the late 1940s, when the region was drawn into China’s civil war. Factions of the retreating nationalist Kuomintang army took control of much of Shan State after the Chinese Communists gained control of the mainland. The nationalist forces brought advanced military equipment and introduced opium cultivation to the economically unviable region, but their presence also led to strengthened alliances between the Chinese Communists and ethnic militias such as the Wa that were campaigning for autonomy in Myanmar. After the Communist Party of Burma was pushed out of power in central Myanmar in the late 1960s, Wa troops joined the Burmese communists in their fight against the government from the north. The Communist Party of China provided support in order to counter the hostility of the Myanmar government.

When the Communist Party of Burma collapsed in 1989 due to an internal rift, Beijing withdrew its support as part of its effort to re-establish ties with the Myanmar central government. In May 1989, the newly established United Wa State Army, which at the time was concentrated primarily around the northern headquarters in the border town of Pangkham, entered a cease-fire agreement with the junta, allowing the government to focus on containing insurgencies elsewhere.

The cease-fire granted the Wa army a high degree of autonomy compared to other ethnic militias in the region, as well as the freedom to expand drug trafficking operations and other business interests that helped the militia fund itself. However, improved relations between Beijing and Yangon, along with enhanced Chinese anti-trafficking efforts, had led to a tightened the Chinese-Myanmar border in the north. This, combined with competition in the drug trade from the expanding Mong Tai Army — an ethnic Shan militia led by local strongman Khun Sa and supported primarily through opium sales — squeezed the Wa army financially and militarily.

When the Mong Tai Army grew more powerful and ramped up rhetoric for an independent Shan republic in the early 1990s, their ambition became unacceptable to the central government. Old enemies — the United Wa State Army and the Tatmadaw — joined forces to counter Khun Sa, resulting in his eventual surrender and retirement in 1996 and the fragmentation of his substantial forces into smaller insurgencies. The move was a strategic triumph for the Wa army, which expanded its southern command and took control of a vast stretch of Mong Tai Army territory along the Thai-Myanmar border in southern Shan State. Tens of thousands of Wa villagers soon relocated from the Sino-Myanmar border to the south. With its territory more than doubled in size, the Wa army was able to open up alternative routes for trade in heroin, raw opium and other goods into Thailand, lessening the Wa’s reliance on trade across the Chinese border.

In the years preceding Myanmar’s “opening” in 2010, the Wa army developed into the most powerful force in northern Myanmar, nearly dominating the eastern bank of Salween River, with exception of certain bases held by the Mong Tai Army’s successor, the Shan State Army-South. The 2007 constitution assembled by the junta even enshrined a Wa autonomous region, comprised of the six townships held by the Wa along the Sino-Myanmar border. In the same way that Khun Sa’s ambition made the Mong Tai Army a target of government forces, the Wa army’s rapid territorial expansion and growing military strength made it an inevitable threat to the Myanmar government, as well as to external powers — most prominently, the United States and Thailand, who shared concerns over the proliferation of drug trafficking (an estimated 60 percent of world’s total heroine production occurred in Shan State) and over insecurity in the Thai-Myanmar border regions. However, the fluid nature of geopolitics in Shan State, the willingness of the Wa to replace poppies with other crops , and the still-potent influence of China, which limited U.S. and Thai power in Shan State, have insulated the Wa army from major threats over the past decade.

Naypyidaw’s Strategy

Since 2011, however, tensions have been heating up in Shan State, with Naypyidaw accelerating its efforts to consolidate the country’s myriad ethnic armies that operate in borderlands where the central government historically has had little control. Now, to support the country’s delicate transition away from international isolation, Naypyidaw has been hoping to establish a sense of national unity and reconciliation — a difficult task considering the highly fragmented nature of the ethnically diverse country. To force the ethnic armies to reconsider their hostilities against Naypyidaw, the government has employed a strategy combining military offensives in restive parts of the country with peace negotiations.

The central government has followed a three-part strategy to contain the Wa: First, the government has attempted to sever lines of communication between Wa’s northern and southern military commands in order to cut off the Wa’s major source of financing and its supply lines to Thailand. The second part of the strategy is to divide Wa forces and their allied ethnic rebels in Shan State in order the gradually encircle the Wa. The third involves expanding the government’s territorial control — either by military or peaceful means — to advance the Tatmadaw’s presence to the eastern bank of Salween River.

The government has at least temporarily neutralized certain ethnic rebel groups in and around Shan State, including the Kachin Independence Army in the north, the Shan State Army-North in the northwest and the Shan State Army-South in the east. The United Wa State Army relied on such militias either for support or to effectively serve as buffers against government encroachment. In the past, the group could at least rely on the other militias’ continued tensions with the central government as a counterbalance.

The Wa’s Strategic Options

Naypyidaw’s current encirclement has the Wa feeling an unprecedented degree of pressure. In June, the Wa began to demand that Myanmar grant it a Wa State on par with other nominally ethnic states such as Mon, Karen, Kachin, and Chin. This would symbolically enshrine the Wa as a key ethnic group in the country, even though it would entail little administrative change. The Wa’s bid was unsuccessful because their current regional competitor, the Shan State Army-South, dispatched representatives to firmly establish their commitment to peace with the government.

Once again Naypyidaw’s central target, the Wa army may seek support from its longtime patron, China, by further integrating itself into Beijing’s broader strategy in Myanmar. In recent years, China has been compelled to resume cultivating influence in northern Myanmar as a way to gain leverage against the central government, which has been attempting to improve relationships with the West in ways that go against Beijing’s interests.

While Beijing still sees the United Wa State Army as a key ally and has every intention to preserve its influence in the border regions, with the strategic importance of Myanmar growing for China, Beijing’s assistance in northern Myanmar will likely be prioritized according to its broader interest in maintaining a regional balance of power and border security. In other words, China will seek to prevent any single player in northern Myanmar from gaining an upper hand.

Fragmentation in Myanmar’s border regions remains the biggest threat to the central government. Nonetheless, a strengthening Tatmadaw is still the most potent long-term threat to the Wa army. Moreover, the Wa leadership is aging. Their passing could lead to a crippling internal rift, and yet another seismic shift in northern Myanmar’s perpetually unstable geopolitical landscape.